“What I can’t understand is, why aren’t people rioting in the streets?” I hear this, now and then, from people of wealthy and powerful backgrounds. There is a kind of incredulity. “After all,” the subtext seems to read, “we scream bloody murder when anyone so much as threatens our tax shelters; if someone were to go after my access to food or shelter, I’d sure as hell be burning banks and storming parliament. What’s wrong with these people?”

It’s a good question. One would think a government that has inflicted such suffering on those with the least resources to resist, without even turning the economy around, would have been at risk of political suicide. Instead, the basic logic of austerity has been accepted by almost everyone. Why? Why do politicians promising continued suffering win any working-class acquiescence, let alone support, at all?

I think the very incredulity with which I began provides a partial answer. Working-class peo- ple may be, as we’re ceaselessly reminded, less meticulous about matters of law and propriety than their “betters”, but they’re also much less self-obsessed. They care more about their friends, families and communities. In aggregate, at least, they’re just fundamentally nicer.

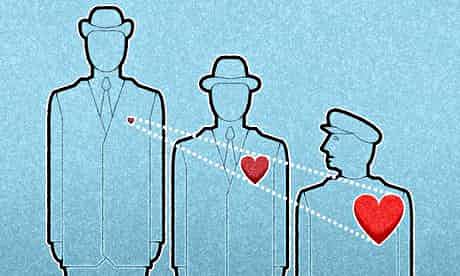

To some degree this seems to reflect a universal sociological law. Feminists have long since pointed out that those on the bottom of any unequal social arrangement tend to think about, and therefore care about, those on top more than those on top think about, or care about, them. Women everywhere tend to think and know more about men’s lives than men do about women, just as black people know more about white people’s, employees about employers’, and the poor about the rich.

And humans being the empathetic creatures that they are, knowledge leads to compassion. The rich and powerful, meanwhile, can remain oblivious and uncaring, because they can afford to. Numerous psychological studies have recently confirmed this. Those born to working-class families invariably score far better at tests of gauging others’ feelings than scions of the rich, or professional classes. In a way it’s hardly surprising. After all, this is what being “powerful” is largely about: not having to pay a lot of attention to what those around one are thinking and feeling. The powerful employ others to do that for them.

And who do they employ? Mainly children of the working classes. Here I believe we tend to be so blinded by an obsession with (dare I say, romanticisation of?) factory labour as our paradigm for “real work” that we have forgotten what most human labour actually consists of.

Even in the days of Karl Marx or Charles Dickens, working-class neighbourhoods housed far more maids, bootblacks, dustmen, cooks, nurses, cabbies, schoolteachers, prostitutes and coster- mongers than employees in coal mines, textile mills or iron foundries. All the more so today. What we think of as archetypally women’s work – looking after people, seeing to their wants and needs, explaining, reassuring, anticipating what the boss wants or is thinking, not to mention caring for, monitoring, and maintaining plants, animals, machines, and other objects – accounts for a far greater proportion of what working-class people do when they’re working than ham- mering, carving, hoisting, or harvesting things.

This is true not only because most working-class people are women (since most people in general are women), but because we have a skewed view even of what men do. As striking tube workers recently had to explain to indignant commuters, “ticket takers” don’t in fact spend most of their time taking tickets: they spend most of their time explaining things, fixing things, finding lost children, and taking care of the old, sick and confused.

If you think about it, is this not what life is basically about? Human beings are projects of mutual creation. Most of the work we do is on each other. The working classes just do a dis- proportionate share. They are the caring classes, and always have been. It is just the incessant demonisation directed at the poor by those who benefit from their caring labour that makes it difficult, in a public forum such as this, to acknowledge it.

As the child of a working-class family, I can attest this is what we were actually proud of. We were constantly being told that work is a virtue in itself – it shapes character or somesuch – but nobody believed that. Most of us felt work was best avoided, that is, unless it benefited others. But of work that did, whether it meant building bridges or emptying bedpans, you could be rightly proud. And there was something else we were definitely proud of: that we were the kind of people who took care of each other. That’s what set us apart from the rich who, as far as most of us could make out, could half the time barely bring themselves to care about their own children.

There is a reason why the ultimate bourgeois virtue is thrift, and the ultimate working-class virtue is solidarity. Yet this is precisely the rope from which that class is currently suspended. There was a time when caring for one’s community could mean fighting for the working class itself. Back in those days we used to talk about “social progress”. Today we are seeing the effects of a relentless war against the very idea of working-class politics or working-class community. That has left most working people with little way to express that care except to direct it towards some manufactured abstraction: “our grandchildren”; “the nation”; whether through jingoist patriotism or appeals to collective sacrifice.

As a result everything is thrown into reverse. Generations of political manipulation have finally turned that sense of solidarity into a scourge. Our caring has been weaponised against us. And so it is likely to remain until the left, which claims to speak for labourers, begins to think seriously and strategically about what most labour actually consists of, and what those who engage in it actually think is virtuous about it.