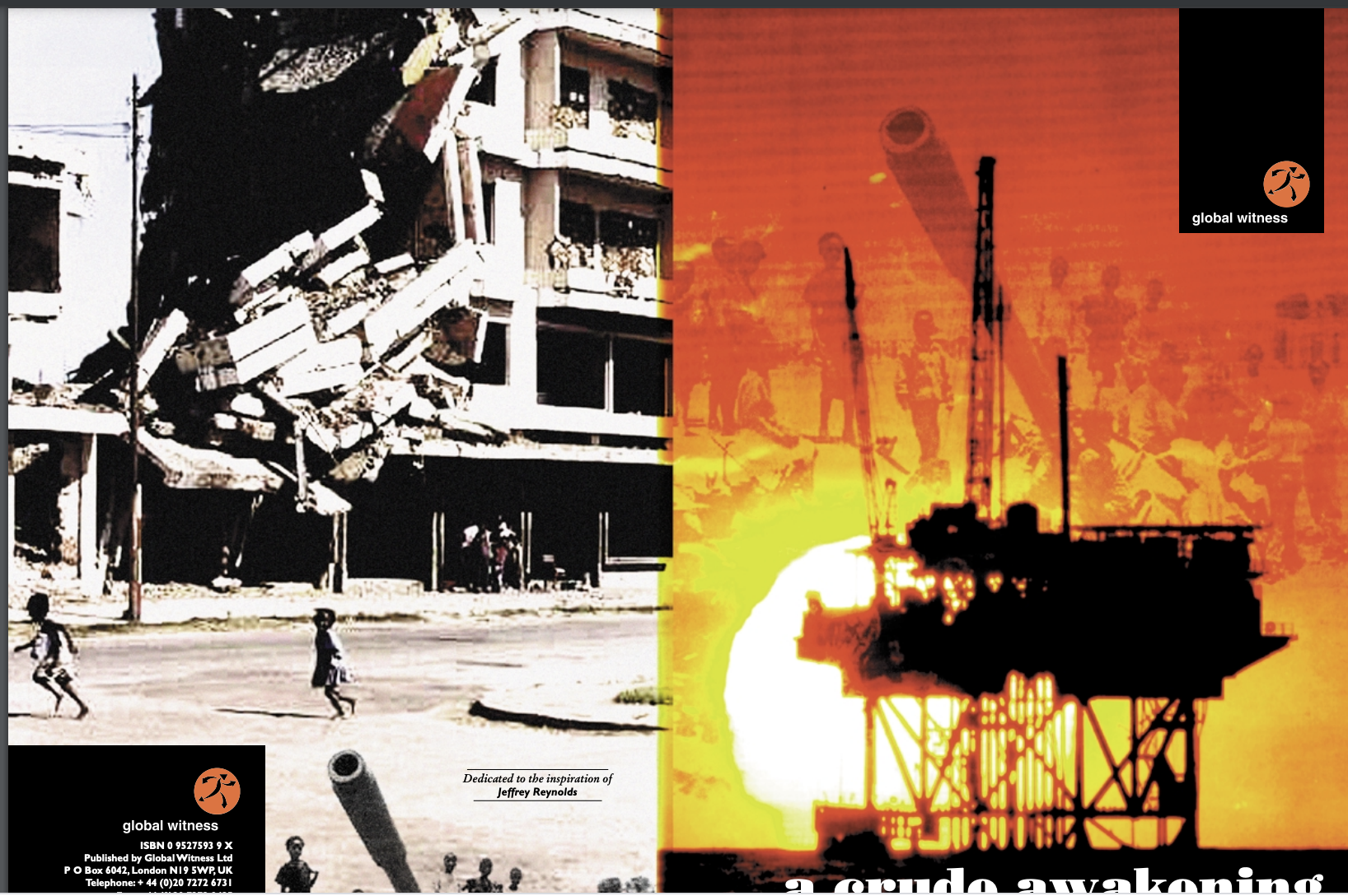

On Saturday, 16th October 2010, some 500 activists gathered at convergence points across Lon- don, knowing only that they were about to embark on a direct action called Crude Awakening, aimed against the ecological devastation of the global oil industry, but with no clear idea of what they were about to do. The plan was quite a clever one. Organizers had dropped hints they were intending to hit targets in London itself, but instead, participants—who had been told only to bring full-charged metro cards, lunch, and outdoor clothing—were led in brigades to a commuter train for Essex. At one stop, bags full of white chemical jumpsuits marked with skeletons and dollars, gear, and lock-boxes mysteriously appeared; shortly thereafter, hastily appointed spokes- people in each carriage received word of the day’s real plan: to blockade the access road to the giant Coryton refinery near Stanford-le-Hope – the road over which 80% of all oil consumed in London flows. An affinity group of about a dozen women were already locked down to vans near the refinery’s gate and had turned back several tankers; we were going to make it impossible for the police to overwhelm and arrest them.

It was an ingenious feint, and brilliantly effective. Before long we were streaming across fields carrying thirteen giant bamboo tripods, confused metropolitan police in tow. Hastily assembled squads of local cops first seemed intent on provoking a violent confrontation—seizing one of our tripods, attempting to break our lines when we began to set them up on the highway—but the moment it became clear that we were not going to yield, and batons would have to be employed, someone must have given an order to pull back. We can only speculate about what mysterious algorithm the higher-ups apply in such situations like that —our numbers, their numbers, the dan- ger of embarrassing publicity, the larger political climate—but the result was to hand us the field; our tripods stood, a relief party backed up the original lockdown; and no further tankers moved over the access road—a road that on an average day carries some seven hundred tankers, haul- ing 375,000 gallons of oil—for the next five hours. Instead, the access road became a party: with music, clowns, footballs, local kids on bicycles, a chorus line of Victorian zombie stilt-dancers, yarn webs, chalk poems, periodic little spokescouncils—mainly, to decide at exactly what point we would declare victory and leave.

It was nice to win one for a change. Facing a world where security forces—from Minneapolis to Strasbourg—seem to have settled on an intentional strategy of trying to ensure, as a matter of principle, that no activist should ever leave the field of a major confrontation with a sense of elation or accomplishment (and often, that as many as possible should leave profoundly trauma- tized), a clear tactical victory is nothing to sneeze at. But at the same time, there was a certain ominous feel to the whole affair: one which made the overall aesthetic, with its mad scientist frocks and animated corpses, oddly appropriate.

The Coryton blockade was inspired by a call from indigenous groups in South America, tied to the Climate Justice Action network, a new global network created in the lead-up to the actions in Copenhagen in December 2009—for a kind of anti-Columbus day, in honor and defense of the earth. Yet it was carried out in the shadow of a much-anticipated announcement, on the 20th, four days later, of savage Tory cuts to the tattered remains of the British welfare state, from benefits to education, threatening to throw hundreds of thousands into unemployment, and thousands already unemployed into destitution—the largest such cuts since before the Great Depression. The great question on everyone’s mind was, would there be a cataclysmic reaction? Even worse, was there any possibility there might not be? In France it had already begun. French Climate Camp had long been planning a similar blockade at the Total refinery across the channel in Le Havre; when they arrived on the 16th, they discovered the refinery already occupied by its workers as part of a nationwide pension dispute that had already shut down 16 of Frances 17 oil refineries. The police reaction was revealing. As soon as the environmental activists appeared, the police leapt into action, forcing the strikers back into the refinery and establishing a cordon in an effort to ensure that under no conditions should the activists be able to break through and speak with the petroleum workers (after hours of efforts, a few, on bicycles, did eventually manage to break through.)

“Environmental justice won’t happen without social justice,” remarked one of the French Climate Campers afterwards. “Those who exploit workers, threaten their rights, and those who are destroying the planet, are the same people.” True enough. “We need to move towards a society and energy transition and to do it cooperatively with the workers of this sector. The workers that are currently blockading their plants have a crucial power into their hands; every litre of oil that is left in the ground thanks to them helps saving human lives by preventing climate catastrophes.” On the surface this might seem strikingly naive. Do we really expect workers in the petroleum industry to join us in a struggle to eliminate the petroleum industry? To strike for their right not to be petroleum workers? But in reality, it’s not naive at all. In fact that’s precisely what they were striking for. They were mobilizing against reforms aimed to move up their retirement age from 60 to 62—that is, for their right not to have to be petroleum workers one day longer than they had to.

Unemployment is not always a bad thing. It’s something to remember when we ponder how to avoid falling into the same old reactive trap we always do when mobilizing around jobs and industry—and thus, find ourselves attempting to save the very global work machine that’s threat- ening to destroy the planet. There’s a reason the police were so determined to prevent any con- versation between environmentalists and strikers. As French workers have shown us repeatedly in recent years, we have allies where we might not suspect we have them.

One of the great ironies of the twentieth century is that everywhere, a politically mobilized working class—whenever they did win a modicum of political power—did so under the leadership of a bureaucratic class dedicating to a productivist ethos that most of them did not share. Back in, say, 1880, or even 1925, the chief distinction between anarchist and socialist unions was that the latter were always demanding higher wages, the former, less hours of work. The socialist leader- ship embraced the ideal of infinite growth and consumer utopia offered by their bourgeois enemies; they simply wished “the workers” to manage it themselves; anarchists, in contrast, wanted time in which to live, to pursue forms of value capitalists could not even dream of. Yet where did anti-capitalist revolutions happen? As we all know from the great Marx-Bakunin contro- versy, it was the anarchist constituencies that actually rose up: whether in Spain, Russia, China, Nicaragua, or Mozambique. Yet every time they did so, they ended up under the administration of socialist bureaucrats who embraced that ethos of productivism, that utopia of over-burdened shelves and consumer plenty, even though this was the last thing they would ever have been able to provide. The irony became that the social benefits the Soviet Union and similar regimes actually were able to provide—more time, since work discipline becomes a completely different thing when one effectively cannot be fired from one’s job—were precisely the ones they couldn’t acknowledge; it has to be referred to as “the problem of absenteeism”, standing in the way of an impossible future full of shoes and consumer electronics. But if you think about it, even here, it’s not entirely different. Trade unionists feel obliged to adopt bourgeois terms—in which pro- ductivity and labor discipline are absolute values—and act as if the freedom to lounge about on a construction sites is not a hard-won right but actually a problem. Granted, it would be much better to simply work four hours a day than do four hours worth of work in eight (and better still to strive to dissolve the distinction between work and play entirely), but surely this is better than nothing. The world needs less work.

All this is not to say that there are not plenty of working class people who are justly proud of what they make and do, just that it is the perversity of capitalism (state capitalism included) that this very desire is used against us, and we know it. As a result, the great paradox of working class life is that while working class people and working class sensibilities are responsible for almost everything of redeeming value in modern life—from shish kebab to rock’n’roll to public libraries (and honestly, do the administrative, “middle” classes ever really create anything?) they are cre- ative precisely when they are not working—that is, in that domain of which cultural theorists so obnoxiously refer to as “consumption.” Which of course makes it possible for the administrative classes (amongst whom I count capitalists) to simultaneously dismiss their creativity, steal it, and sell it back to them.

The question is how to break the assumption that engaging in hard work—and by extension, dutifully obeying orders—is somehow an intrinsically moral enterprise. This is an idea that, ad- mittedly, has even affected large sections of the working class. For anyone truly interested in human liberation, this is the most pernicious question. In public debate, one of the few things everyone seems to have to agree with is that only those willing to work—or even more, only those willing to submit themselves to well-nigh insane degrees of labor discipline—could possi- bly be morally deserving of anything—that not just work, work of the sort considered valuable by financial markets—is the only legitimate moral justification for rewards of any sort. This is not an economic argument. It’s a moral one. It’s pretty obvious that there are many circumstances where, even from the economists’ perspective, too much work and too much labor discipline is entirely counterproductive. Yet every time there is a crisis, the answer on all sides is always the same: people need to work more! There’s someone out there working less than they could be—handicapped people who are not quite as handicapped as they’re making themselves out to be, French oil workers who get to retire before their souls and bodies are entirely destroyed, art students, lazy porters, benefit cheats—and somehow, this must be what’s ruining things for everyone.

I might add that this moralistic obsession with work is very much in keeping with the spirit of neoliberalism itself, increasingly revealed, in these its latter days, as very much a moral enterprise. Or I think at this point we can even be a bit more specific. Neoliberalism has always been a form of capitalism that places political considerations ahead of economic ones. How else can we understand the fact that Neoliberals have managed to convince everyone in the world that economic growth and material prosperity are the only thing that mattered, even as, under its aegis real global growth rates collapsed, sinking to perhaps a third of what they had been under earlier, state-driven, social-welfare oriented forms of development, and huge proportions of the world’s population sank into poverty. Or that financial elites were the only people capable of measuring the value of anything, even as it propagated an economic culture so irresponsible that it allowed those elites to bring the entire financial architecture of the global economy tumbling on top of them because of their utter inability to assess the value of anything—even their own financial instruments. Once one cottons onto it, the pattern becomes unmistakable. Whenever there is a choice between the political goal of undercutting social movements—especially, by convincing everyone there is no viable alternative to the capitalist order–and actually running a viable capitalist order, neoliberalism means always choosing the first. Precarity is not really an especially effective way of organizing labor. It’s a stunningly effective way of demobilizing labor. Constantly increasing the total amount of time people are working is not very economically efficient either (even if we don’t consider the long-term ecological effects); but there’s no better way to ensure people are not thinking about alternative ways to organize society, or fighting to bring them about, than to keep them working all the time. As a result, we are left in the bizarre situation where almost no one believes that capitalism is really a viable system any more, but neither can they even begin to imagine a different one. The war against the imagination is the only one the capitalists seem to have definitively won.

It only makes sense, then, that the first reaction to the crash of 2008, which revealed the fi- nanciers so recently held up as the most brilliant economic minds in history to be utterly, disas- trously inept at the one thing they were supposed to be best at— calculating value–was not, as most activists (myself included) had predicted, a rush towards Green Capitalism—that is, an eco- nomic response—but a political one. This is the real meaning of the budget cuts. Any competent economist knows what happens when you slash the budget in the middle of downturn. It can only make things worse. Such a policy only makes sense as a violent attack on anything that even looks like it might possibly provide an alternative way to think about value, from public welfare to the contemplation of art or philosophy (or at least, the contemplation of art or philosophy for any reason other than making money). For the moment, at least, most capitalists are no longer even thinking about capitalism’s long-term viability.

It is terrifying, to be sure, to understand that one is facing a potentially suicidal enemy. But at least it clarifies the situation. And yes, it is quite possible that in time, the capitalists will pick themselves up, gather their wits, stop bickering and begin to do what they always do: begin pilfering the most useful ideas from the social movements ranged against them (mutual aid, de- centralization, sustainability) so as to turn them into something exploitative and horrible. In the long term, if there is to be a long term anyway, they’re pretty much going to have to. But in the meantime, we really are facing a kind of kamikaze capitalism—a capitalist order that will not hesitate to destroy itself if that’s what it takes to destroy its enemies (us). If nothing else it does help us understand what we’re fighting for: at this moment, absolutely everything.

This makes it all the more critical to figure out a way to snap the productivist bargain, if we might call it that—that it is both an ecological and a political imperative to bring about that meeting that the police in Le Havre were so determined to prevent. There are a lot of threads to be untangled here, and any number of pernicious illusions that need to be exposed. I will end with only one. What is the real relation between all that money that’s supposedly in such short supply, necessitating the slashing of budgets and abrogation of pension agreements, and the ecological devastation of our petroleum-based energy system? Aside from the obvious one: that debt is the main means of driving the global work machine, which requires the endless escalation of energy consumption in the first place. In fact, it’s quite simple. We are looking at a kind of conceptual back-flip. Oil, after all, is a limited resource. There is only so much of it. Money is not. A coin or bill is really nothing but an IOU, a promise; the only limit to how much we can produce is how much we are willing to promise one another. Yet under contemporary capitalism, we act as if it’s just the opposite. Money is treated as if it were oil, a limited resource, there’s only so much of it; the result is to give central bankers the power to enforce economic policies that demand ever more work, ever increasing production, in such a way that we end up treating oil as if it were money: as an unlimited resource, something that can be freely spent to power economic expansion, at roughly 3–5% a year, forever. The moment we come to terms with the reality, that we are not dealing with absolute constraints but merely promises, we can no longer say “but there just isn’t any money”—the real question is who owes what to whom, what sort of promises are worth keeping, which are absolute—a government’s promise to repay its creditors at a predetermined rate of interest, or the promise that it’s workers can stop working at a certain age, or our promise to future generations to leave them with a planet capable of human habitation. Suddenly the morality seems very different; and, like the French environmentalists, we discover ourselves with friends we didn’t know we had.