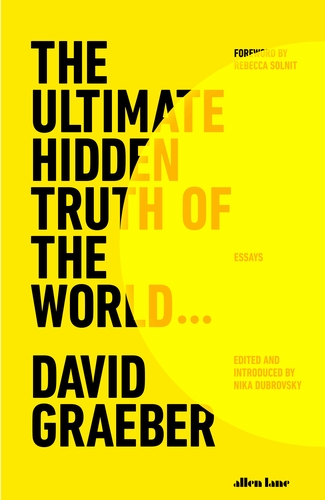

The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World by David Graeber: Intense flares of thought from a brilliant mind

This chunk of writing spanning 30 years provides an ideal entry point to new readers of Graeber, while for those returning to his ideas, the pleasure is in the writing

You would hardly think that watching daily news broadcasts these days could be smile-inducing. Yet I can’t help but picture the smiling face of anthropologist, anarchist activist, and feminist David Graeber. I hear his sorely-missed voice also, giggling and reminding us how the establishment in their unblinking delusion continue to tell (ie patronise) us that the way we live, and have lived for the past 250 years, is the only system that works. Imagining anything else would be chaos. Well, we wouldn’t want to be living in a chaotic world right now, would we?

In his thinking Graeber always cut through the chaos, gave power to the imagination, and usually retrieved some sense out of the senseless. In these ambitious and erudite essays, he writes: “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.” This is a key to reading Graeber: while others talk of impossibilities he looked to the possible, helping us prefigure how the world could be unmade to be made better.

Being part of the global justice movement and Occupy Wall Street brought the New York-born academic to a wider public prominence, as did books such as Debt: The First 5,000 Years and essays such as Bullshit Jobs, which went viral when it was written for a small online magazine, Strike!. That essay is included here, and like much of the rest of the book, can be found readily in the public domain.

But this does not diminish Ultimate Hidden Truth, as collecting a chunk of Graeber’s writing spanning 30 years from similar niche publications (his work for larger outlets, The Guardian, Harper’s magazine, etc also features) will provide an ideal entry point to new readers perhaps unlikely to stumble upon his work unless at the mercy of algorithms. For those returning to his ideas, the pleasure is in the writing, filled as it is with historical heft, global prescience, and a vast breadth of reference by the seemingly omniscient author.

How about this koan-esque take on capitalism: “It is a system that can renew itself only by cultivating a hidden pleasure at the prospect of its own destruction.” Or if you are still somehow perplexed at how the recent US presidential elections played out, here is Graeber two decades ago pointing out why the exclusion of the working class in American education has deepened divisions in the binary system ever further. The names have changed, but the formula feels all too familiar: “If working-class (GW) Bush voters tend to resent intellectuals more than the rich,” he writes, “the most likely reason is that they can imagine scenarios in which they might become rich, but cannot imagine one in which they, or any of their children, could ever become a member of the intelligentsia. Such structures of exclusion (in education) had always existed, of course, especially at the top, but in recent decades fences have become fortresses.”

At times it feels like Graeber had read everything possible there ever was for him to read. In one essay he’s discussing philosophers using lobsters as a paradigm for consciousness, while throwing in the tickling titbit of Jean-Paul Sartre becoming erotically obsessed with crustaceans after ingesting too much mescaline.

Graeber’s life felt unfairly fugacious with the shock of his death at the age of 59 in 2020; followers of his work felt like they had been robbed, as a world with him in it was always a richer one.

But the reflections of a brilliant mind through the words he has left behind will endure, and this book is a welcome start to an archival project. Graeber’s essays remain intense flares of thought lighting a path towards something better than “the best of all possible worlds”, which is a place where we all too readily resign ourselves.