BEYOND THE MONASTIC SELF: JOINT MIND AND THE PARTIAL ILLUSION OF INDIVIDUATION

In this short essay, David discusses how a very questionable idea, about the nature of human consciousness, shapes the academic world into a machine for producing "great minds" and, in the end, justifies social structures of inequality.

One of the things I most admire about Maurice Bloch is that he’s never forgotten what got him interested in anthropology to begin with. Most of us do. How many after all are drawn to the discipline above all curious about questions that only it can answer: questions like, what are humans, in what ways are they the same, in what ways are they different? It’s one of the peculiar perversities of graduate and professional training that we often forget this, and one of the perversities of this peculiarly anti-theoretical moment that there are prominent figures telling us we should forget them. Because to reject these questions out of hand is not only to reject the very premise of anthropological theory, but for anthropology to be able to offer any explanation of its own existence—to be able to ask (to adopt a phrase from Roy Bhaskar, originally about experiments), both “what makes anthropology possible”—why do we even have the capacity to understand someone living in rural Madagascar, but also, simultaneously, “what makes anthropology necessary” why that understanding is usually not transparent, and in so many respects, extraordinarily difficult.

I want to address this by looking at what has always been the primary anthropological method: conversation. Actually, I would argue it’s not only our primary fieldwork method, but our primary method of coming up with new theoretical ideas. Good ideas rarely, if ever, emerge from isolation. True, often these theoretical dialogues are not carried out face to face—I myself have been engaged in a series of theoretical conversation with Maurice Bloch for decades now, even though we’ve surprisingly rarely sat together in the same room and hashed matters out directly. One of our peculiar fetishistic habits, as intellectuals, is to efface the histories of most of these conversations after they’ve happened, or at best carve up the results, so as to make it seem like ideas emerge from isolated Great Thinkers. But in practice we’re all aware, on some level, this is never really true: I have no idea, for instance, the degree to which many of the ideas attributed to me are the product of me, or some of my graduate student friends with whom I spent long hours hashing out the meaning of the universe twenty years ago, and ultimately I think it’s a meaningless question: the ideas emerged from our relation.

The process of the collective, or dialogic emergence of ideas in turn involves certain techniques, which only make sense in terms of a larger context of exchange and answerability. One of these is the provocation. An intellectual provocation, as we all know, usually consists of a statement that makes sense from a certain theoretical perspective that so clashes against received wisdom that it will inevitably spark a debate from which new richer understandings are likely to emerge. An example might be: poetry is an impoverished form of speech. Maurice as we all know is a master of this and as a discipline we’ve gained much from the results, so it seems to me the best way to honor him is to attempt in my own small way to do the same.

So I will propose one. It might be considered an expansion on some arguments Maurice himself made in an essay calling “Going in and Out of Each Other’s Bodies,” on the ambiguities of “the distinctness of the units of life,” including human beings, and which draws on the findings of neuroscience to observe the fact that this includes “the interpenetration of minds” which, during acts of communication, involves a kind of mind-reading in which identical neuronal configurations are occurring in the brains of both parties, so that, in a certain—however limited—sense, they can be seen as part of a single configuration, mediated by some kind of physical bridge (of sound waves, bodily movements, images, whatever.) It strikes me almost no one has really considered the full implications of this. Bloch makes some excellent points about the sense of human solidarity (what I’ve myself referred to as “baseline communism”) emerging in part from cumulative awareness of this sort of practical mutual interpenetration, and the fact that the very possibility of human life is built on it, but for the moment I want to take it another way. I want to suggest that almost all existing social theory is based on a misapprehension. We tend to veer between looking at individuals and societies, transcendental subjects and meaningful universes, where in fact, particularly when it comes to questions of conscious thought, we are really speaking of something that occurs not in one person’s head but within just these dyadic or if you like “intersubjective” relations. To put it more starkly: thinking—or, anyway, conscious, self-reflective thought—does not mainly happen in the head. Neither does it mainly happen in our relations with our material environments, as some have recently proposed, or in some great abstract collective consciousness. Consciousness exists mainly in concrete junctures between what have sometimes been called “embodied personalities.”

In other words it’s not just our folk theories of how the mind works that are wrong. It’s our folk theory about what the mind is that’s wrong. This means

*

The usual response to such a statement is either to say “that’s insane” or “but of course we already know that”—which as we know are both equally modes of dismissal, since in fact the people saying this don’t know this, they just think they know it, since this “knowledge” has no effect on anything else they say or do. (Consider the case of the rather similar ideas that emerged from conversations amongst the Bakhtin circle in ‘20s Russia; how many scholars claim to agree with them that thought is dialogic, and then act as if all the ideas that emerged from their dialogues were the product of one individual genius, Mikhail Bakhtin.)

Let me start with the subject of consciousness. There has been a burst of publications in the last decade by social theorists trying to come to terms with the findings of cognitive science, which might be summed up as, “consciousness isn’t all its cracked up to be”—that in much of our daily existence and activities, in fact, we might as well be sleep. In what follows I’ll take just one—but I should emphasize this is for ease of exposition only; I could just as easily have chosen at least a dozen others to make the same point.

In a recent essay, geographer Nigel Thrift (2006:285) argues of intellect itself that “research over many years has shown that it is at best a fragile and temporary coalition, a tunnel which is always close to collapse.” He continues by quoting Mervin Donald, one of the many contemporary philosophers to engage with the findings of cognitive psychology on the nature of that classic philosophical object, consciousness:

During the past forty years, in countless laboratories around the world, human consciousness has been put under the microscope, and exposed mercilessly for the poor thing it is: a transitory and fleeting phenomenon. The ephemeral nature of consciousness is especially obvious in experiments on the temporal minima of memory- that is the length of time we can hold on to a clear sensory image of something. Even under the best circumstances, we cannot keep more than a few seconds of perceptual experience in short-term memory. The window of consciousness, defined in this way, is barely ten or fifteen seconds wide. Under some conditions, the width of our conscious window on the world may be no more than two seconds wide (Donald 2001: 15)

The question, then, becomes: how is it that we come to the representation of the subject typical of Western philosophy, and which forms the basis of all social science, as a fundamentally conscious, rational, intentional, self-aware—one which appears to bear almost no resemblance to any actual living human being?

The answer I think goes back to the origins of philosophy itself. One of the remarkable things about the evolution of philosophy is that just about everywhere we first encounter it, it is characterized by two features which are gradually lost. One is that its intellectual arguments are typically couched in the form of dialogues and conversations. The second is that it is not considered a mere matter of reflection, but a form of practice: as Pierre Hadot (1995, 2002) has long since pointed out, not only Buddhism, Confucianism, or Taoism, but even Greco-Roman schools like the Stoics and Epicureans promulgated forms of meditation, diet, exercise, sexual practice or continence, essentially ways of training the mind and body so as to create a form of fully self-conscious subject. In other words, isolated, self-sufficient, rational, self-reflective intellect was not assumed as the starting-point; it was, rather, a telos; the ideal end point of a long and painful process which no ordinary mortal, really, could ever be expected to fully achieve.

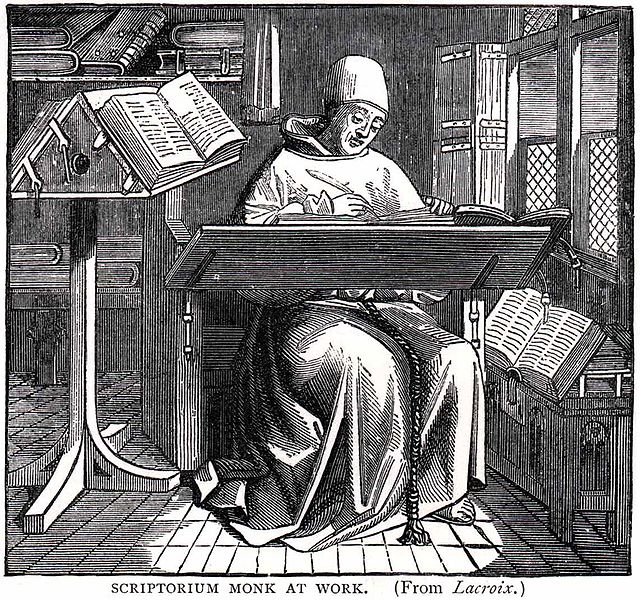

What happened? Perhaps it is best considered as an example of what I’ve elsewhere called “liberation in the imaginary.” It is not uncommon to observe such patterns in intellectual life. In its early days, for instance, cultural studies was seen as a theoretical tool for revolutionaries, a way of facilitating working class resistance against dominant values. Gradually it became a purely academic pursuit that started from the assumption that all working class people were already engaged in one or another form of semiotic resistance to dominant values. It would seem something very similar happened to our philosophical tradition, when it moved from the monastery to the university, and therefore ceased to conceive itself as a form of practice—except on a much grander scale. As a result, even after they abandoned the monastery, scholars maintained what was essentially a monastic self.

*

What I’d really like to emphasize here is a remark that appears really as an aside in Thrift’s argument: he notes, true, “This description [of consciousness] is something of an exaggeration – it derives from laboratory experiments and glosses over the richness of joint action in which subjects do much better” (ib:285). In other words, even if the window of consciousness is typically a few seconds long when one is by oneself, with others, it’s much broader.

When I first read this passage I thought he was referring to primarily to conversation. After all, while mindless conversations certainly exist, we are all also aware that we’ve had conversations (with loved ones, or, on exciting topics) where we were quite vividly conscious for hours at a time. During one such vivid phone conversation with my girlfriend a few weeks ago, she suggested, “yes—that’s why they say that when you’re driving and afraid you’re going to fall asleep, the best thing to do is to talk to someone else. Just listening to talk radio won’t do it”—making her incidentally one of the effective co-authors of this piece. If we are really talking about differences on the magnitude of seconds versus hours, it’s clear that the vast majority of our fully conscious life is spent discussing things with others.

On some level this too should be self-evident. One need only consider the etymology, which is con-science, which literally means, “knowing things together.” But nonetheless, when I then went to consult the vast literature on consciousness, starting with grand compendia like The Oxford Companion to Consciousness, for example, I discovered that there was almost nothing there on conversation at all. In most works on the subjects, words like “dialogue” and “conversation” barely appear. For the most part, the discussion is limited to “internal speech,” imaginary conversations one has in one’s head—the existence of this could be taken of course as dramatic affirmation of the degree to which conscious thought requires interlocutors, but rarely is. The great exception here of course is that—in psychology, very much subordinate—strain of theory that hearkens back to the Soviet Union in the 1920s: Vygotsky’s work on egocentric speech in children, whereby he showed that abstract thinking is made possible by internalizing verbal interaction with the outside world, and of course the work of the Bakhtin circle. Bakhtin’s argument that consciousness is the voices of others speaking in your heads is perhaps the most radical statement in this respect—but it’s now considered distinctly marginal, relegated to a small school of Bakhtin-studies; partly because of its now-outmoded premise that the only possible medium for thought is language, but largely, I suspect, because of the larger political content of the argument, with the clash between voices of authority and their carnivalesque subversion. What’s more, for all the importance they attach to dialogue as the essence of human thought, neither the Vygotsky or Bakhtin schools spend much time at all discussing actual conversations, that is, dialogues between two or more mature individuals, as opposed to virtual dialogue in the mind or works of literature.

My suspicion is no one really wants to address the matter because the consequences threaten to unsettle everything—including, as I say, our very presumptions about the objects of our study. Let me give an example. Work on “distributed cognition,” the idea that in many circumstances, thinking takes place outside the individual head, going back to Edwin Hutchins’ analysis of how each member of a ship’s crew “offloads” different aspects of navigation to each other, and how they, together with the ship’s machinery, themselves form of a kind of larger cognitive machine. Yet with only a few exceptions (mainly by those extending Vygotsky’s insights in the field of education), the field has tended to concentrate increasingly on the technological aspect: in our reliance (and therefore trust) in machines as extensions of ourselves rather than our reliance on each other.

This becomes strikingly true when these ideas are taken up by philosophers. Andy Clark for instance has become famous for developing what’s often known as the “extended mind hypothesis”—asking, why is it we assume that our minds are coincident with the physical material of our brains. If minds are dynamic processes of thinking, this is obviously not the case. If one person can do long division in their heads, and another must make recourse to paper and pencil, the brain cells, and the paper and pencil, are playing exactly the same role—it’s simply incoherent and arbitrary to insist that there is a fundamental distinction between them. Or to take a more ethnographic example: traditional Malagasy houses are all organized on the same pattern, with 12 astrological positions mapped out from the northeast corner clockwise, so that if one is sitting in the main room it’s possible to make astrological calculations just by glancing from hearth to water-pot to back door, etc. Clearly on such an occasion, the house is part of one’s extended mind. This position seems largely accepted now within the philosophical community, but the logic is applied, almost exclusively, to technologies—especially computers, as in Clark’s own most famous book, “Natural Born Cyborgs.” There’s something obviously missing here. If thought, including conscious thought, is really a the interaction of brain, body, and one’s environmental (and of course, culturally constituted) “cognitive scaffolding”—well, what about other brains? In his original essay on the extended mind, Clark and fellow philosopher David Chalmers are willing to entertain the possibility, though as always he frames it in a way that seems calculated to sidestep the most serious implications: he notes, some people memorize names and phone numbers, some people put them in little books, but there’s one basketball coach notorious for always relying on his wife. Surely, her memory is part of his cognitive scaffolding, just like a waiter who might remember what sort of sauce I like. True, but in a purely passive way—much as Roman senators notoriously tended to keep a favorite slave constantly at their side, whose job was to remember the names, faces, office, and personal or political significance of all their friends and colleagues.

If we apply the same insight to more active forms of engagement between what we call “minds”, we can see why the philosophical implications might be unsettling. When we speak of the coordination of neuronal processes between brains, are we just speaking of a kind of “mind-reading,” as Bloch puts it, or the creation—at least at the point of understanding—of a single mind? If minds are processes of interaction not limited to the brain, then this pretty much has to be the case. Yet the only philosopher I know who has fully embraced this point is the philosopher of science, Roy Bhaskar, and it would seem he has only been able to do so by abandoning the strictures of academic philosophy entirely and returning to the older idea of philosophy as inseparable for techniques for achieving freedom and self-consciousness rather than describing it, a project which has meant active engagement with Buddhist and Taoist and similar traditions that still operate in such terms, and, being written off as a New Age flake or raving lunatic even by many of his formerly most ardent disciples. The argument though is fascinating. You will recall here that historically, that creature we now think of as the self-conscious individual was largely created through disciplinary techniques of isolation and reflection. Such techniques also, in a sense, created a certain notion of the cosmos, of totality, against which the individual was posed; and having created the difference, the final step was often exploding it again by some mystical experience of cosmic unity, often framed as unity with God. This entailed the recognition of what in the Sanskrit tradition came to be known as “non-dualism”, that atman and brahman, self and cosmos, however it was framed in that particular tradition, were the same. All Bhaskar does is argue that you don’t actually need to sit on a mountain and beat yourself with thorns for twenty years in order to have a mystical experience. In a certain sense, any time you understand what someone else is trying to communicate to you, you are having a direct experience of non-dualism, of a unity between minds which is a direct result of the underlying unity of all physical processes, which make it possible for the mirror neurons in our brains to fire in the same way, for more or less the same reasons outlined above. Our very existence as intelligent beings is made possibly by an endless variety of minor, everyday mystical experiences, that occur between “embodied personalities” (his phrase originally) rather than between some abstract, artificially created “self” and cosmos.

*

If anyone should doubt the devastating implications if we apply the extended mind hypothesis to dialogic consciousness, consider the following four points, which, alas, can only be sketched out very briefly:

1) one of the classic problems in Western philosophy is the so-called “other minds problem.” Starting from the Cartesian cogito, how can we be certain other minds exist? Actually, we can’t start from the Cartesian cogito, because the fact that we think does not prove we exist as autonomous minds already separate from other ones; the real problem is the joint relational work we do constructing situations in which we can think of ourselves as autonomous selves—a work of which the monastic disciplines of the ancient philosophers (which did require the help of other people: especially, again, slaves) are simply particularly extreme examples.

2) Or consider hermeneutics. We are used to assuming that interpretation is the work required on the part of an audience, the recipient of an intentional act communication, to imaginatively identify with its author, thus, effectively, creating the author as the imaginatively recreated intentional agent whose will is assumed to bind all the different elements in the message together. But if at the moment of communication speaker and listener, author and reader, are actually the same mind, then what we are really witnessing is the act of creating a separation.

3) Similarly, while we are willing to accept that individuation in childhood involves a shared conceptual labor of teaching children to distinguish themselves from others and the surrounding world, we assume that this is simply the recognition of a truth and that the process ends when this truth is realized, it would appear this is not really the case. It is at best a half-truth, and for this reason the process of individuation never really ends, the illusion, one might say, must be endlessly maintained. What’s more, there is generally a decidedly political aspect to this, since, the very most basic form of exploitation would seem to be the process whereby one end of such nexi individuates itself at the expense of another, rendering the other in a strange state somewhere between individuation, empathy, and nonexistence.

4) Finally, there is the voluminous literature on the Other—you know, the one with the capital O—that runs from Hegel’s master slave dialectic through Kojeve, Sartre, Fanon and De Beauvoir, on through its endless refractions in the present day. On the one hand, the dialectical tradition from which this derives might seem to be one that actually is aware of the ultimate identity of subject and object, and provide tools for understanding this constant process of (often exploitative) individuation; but here again, there is again the difference between knowing something, and just thinking you know it—since as the dialectical tradition itself is famous for emphasizing, knowledge is not knowledge unless it’s put to work. A century ago now, Lukacs was already pointing out the philosophers have to continually rediscover the fact that persons are really relations, just as things are really processes, because in a system where the commodity form dominates, the simple realization is meaningless, it has no effect. What I will leave then with is only this. The very notion of dialectics originally derives from the Socratic method, and that, from the peculiar form of so much ancient philosophy: to use the dialogic form to create the ideal of a self-reflexive consciousness that might transcend dialogue. (The result, as we all know from Plato, is a peculiar one-sided form of dialogue, one which Hegel, drawing, interestingly, on the non-dualistic assumption that the structure of argument and that of even natural phenomenon are ultimately one, subsumed into the mind of a cosmic Reason attempting, again like an ancient philosophy student, to carry out a series of exercises designed to ultimately achieve a fully self-reflexive state.) In other words, in its classical form at least, it ultimately aims to liberate us from the very situation I’ve been describing into a totality whose political implications have tended to be perilous at best.

But what would a politics, an ethics, a science, look like that did not run away from this situation, but simply embraced it: that turned our received understandings inside out, and then, proceeded from there? We have hardly really begun to ask.