Noam Chomsky on David Graeber’s Pirate Enlightenment

ArtReview

Nika Dubrovsky speaks to Noam Chomsky about pirate societies, ‘bewildered herds’ and the fragility of the present in the context of the late anthropologist David Graeber’s final book

As questions of decolonisation rub up against the legacy of Enlightenment thinking in the West, anthropologist David Graeber argues in his posthumous book Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia (to be published early next year) that Enlightenment ideas themselves are not intrinsically European and were indeed shaped by non-European sources. The work focuses on the proto-democratic ways of pirate societies and particularly the Zana-Malata, an ethnic group formed of descendants of pirates who settled on Madagascar at the beginning of the eighteenth century, and whom Graeber encountered while conducting ethnographic research at the beginning of his academic career.

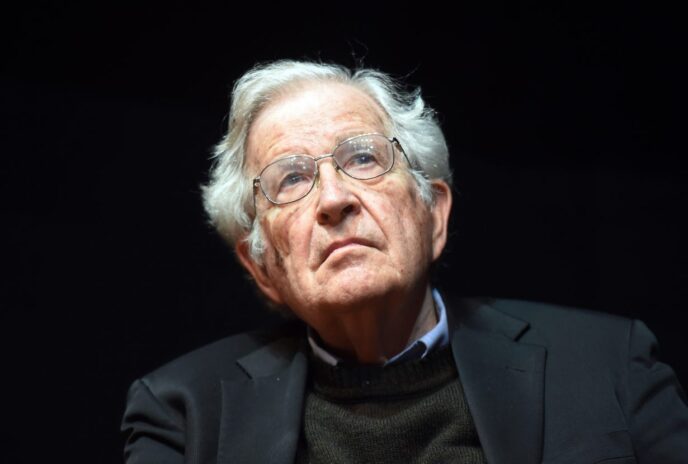

Graeber, author of Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (2018), Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011) and The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (written with the archaeologist David Wengrow), died in 2020, but in a wide-ranging conversation for ArtReview, his widow, the artist and author Nika Dubrovsky, speaks with Noam Chomsky, an admirer of the anthropologist’s work, about Graeber’s last project, neoliberalism and democracy, Western empiricism and imperialism, free speech, Roe v. Wade in the US, the war in Ukraine and how Germany’s Documenta art exhibition has barely coped with inviting non-Western artists to direct it for the first time.

One of the left’s foremost thinkers, Chomsky has written major works that include Syntactic Structures (1957), Manufacturing Consent (1988) and, most recently, The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and Urgent Need for Radical Change (2021, with C. J. Polychroniou).

David Graeber. Courtesy Goldsmiths, London

Nika Dubrovsky Thank you very much for the interview. It’s a great honour. We wanted to discuss David’s last posthumous book, Pirate Enlightenment, which will be published in January 2023 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In this book, as in his other writings, David talked about the importance of dialogue. He describes how entire cultural traditions emerge from the creation of new stories and how these traditions are then remade and edited.

Noam Chomsky That was very interesting. Both in his essay ‘There Never Was a West’, but also in the book about the extensive contributions of Native American thinkers [The Dawn of Everything, 2021, with David Wengrow], Chinese thinkers and others who, as they point out, as David points out, were recognised as contributors at the time, but then wiped from the tradition. It was regarded as just a literary technique or something. But I think he makes it very clear that it was a substantive contribution.

The discussion in ‘There Never Was a West’, about the nature of influence, was quite enlightening. The different ways in which influence takes place, in which it’s interpreted, and – as the tradition is constructed later – is filtered out, as he points out, on the basis of arguments that, if they were applied generally, would wipe out almost everything, including the tradition itself.

One of the most interesting parts of The Dawn of Everything, I thought, were the sections on the interactions with the Native American philosopher and thinker, and his contributions to how Enlightenment thought was developed by leading figures.

ND Just before Thomas Hobbes wrote Leviathan, he had seen a play by Charles Johnson, The Successful Pyrate, performed on an English stage. David suggested that this experience with Madagascar pirates may have influenced Hobbes’s political thinking. The very idea that people could negotiate with each other; that power could be organised not only top-down but also horizontally, as it was in many pirate communities, and in some indigenous cultures, came as a surprise to Europeans. David often said that his task was to decolonise the Enlightenment; to change our ideas of what kind of society we would like to live in. If we rethink our ideas about the Enlightenment, about where it came from, how do you think this will change the public imagination?

NC I think we must pursue more carefully these insights into how that tradition, as he points out, becomes the reconstruction of the past by elite thinkers who reshape it into a particular form. But when you go back to the original interactions, as David did and as they do in The Dawn of Everything, you see that what was filtered to become the accepted tradition is a sharp reconstruction of what actually happened – eliminating many interactions and many kinds of drawing on different voices, different experiences into something that was then reshaped by elite opinions.

Particularly striking, I think, was his discussion, in ‘There Never Was a West’, of periods when state authority was inoperative for one reason or another, either not paying attention or weakened. It’s at that time that interactions at the ground level developed the basic meaningful contributions to whatever functions later as democracy.

That’s where they arose, that’s how they can develop. But not the top-down conceptions that are reconstructed as our traditional heritage. It has lots of implications for direct action in the present. I think his emphasis is on things like the Zapatistas in the past, on relatives, work on pirates and so on. Pirate democracy in Madagascar and others is quite striking in that respect.

A Betsimisarakian henhouse and rice barn, 1911, Fenerive, Madagascar, photo: Walter Kaudern. Public domain. A subset of the Betsimisaraka, termed the zana-malata, were the focus of David Graeber’s dissertation research, from which Pirate Enlightenment is derived

ND In the Malagasy society that David lived in for several years and knew very well, dialogue is used as a political tool to shape public space. In your book Manufacturing Consent [1988, with Edward S. Herman], you describe how public space and the public imagination in Western countries is controlled from the top down by powerful ideological institutions.

NC Ed Herman, who passed away recently, was the prime author of that. He was a specialist in finance and taught at the Wharton School. He was interested in the institutional structure of the media and how basic institutional factors lead to the shaping of the information system that’s created. We slightly differed on that, I should say. My own feeling is that while all of that is important, I don’t think it’s very different from the general intellectual culture. My own work has mostly been, actually, on elite intellectual culture, which doesn’t have those same institutional pressures, but nevertheless leads to a version of reality that’s not very different from what comes out of the media system.

The phrase ‘manufacturing consent’, of course, is not ours. That comes from [American political commentator] Walter Lippmann. Also Edward Bernays, the main founder of the public relations industry. The two of them were members of Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Information, the first major state propaganda agency, the so-called Creel Committee, which was designed to try to turn a pacifist population into raving anti-German fanatics as the Wilson administration moved into the war.

Both Lippmann and Bernays were very impressed by the success in creating a fabricated version of atrocities and so on, which in fact did change opinion dramatically. Lippmann called this technique ‘manufacturing consent’, which he called a new art in the practice of democracy. He thought that’s exactly the way things should work.

As David points out in his text, elite opinion has always been radically antidemocratic all the way through. Democracy is just regarded as ‘mob rule’, as Lippmann put it; the responsible men have to protect themselves from the roar and trampling of the bewildered herd. Lippmann, incidentally, was the leading liberal public intellectual in the twentieth century, a Wilson, Roosevelt, Kennedy liberal. But he was reflecting the general liberal conception of how the public has to be put in its place as spectators, while the serious guys – us – do the work of running society in the public interest.

This is almost universal. It’s not just in the media. People like Reinhold Niebuhr [an American theologian] and Harold Lasswell, one of the pioneers of modern political science. Bernays went on to be one of the founders of the public relations industry, which devotes hundreds of billions of dollars a year to these efforts to control opinion and attitudes. But it’s all based on the same conception that the public is a bewildered herd, stupid and too ignorant for their own good.

You have to control them in one way or another, not permit democratic tendencies. Perhaps you know the major scholarly work, the gold standard for scholarship on the Constitutional Convention, called The Framers’ Coup [2016, by Michael Klarman], the coup by the framers against democracy. They feared democracy, and they devised all kinds of techniques to prevent it effectively. If you look back at the Constitutional Convention, the only participant who objected to this was Benjamin Franklin. He went along, but he didn’t like it.

Yes, it is correct that this shows up in the media, but it seems to me to show up in the media not only because of the institutional structures that Herman’s work mostly outlined but also because of deeper currents in cultural history. It’s the same thing in the English Revolution in the seventeenth century when you didn’t have these structures, ‘The Men of the Best Quality’, as they called themselves, must subdue the rebel multitude.

When you read the history of the English Revolution, it looks as if it was a conflict between king and parliament, but that overlooks the public who were producing very extensive pamphlet literature and people travelling around giving talks and so on. They didn’t want to be ruled by a king or parliament. The way they put it was, “We want to be governed by people who know the people’s sores, people like us, not by knights and gentlemen who do just want to oppress us”. That’s the English Revolution, the major current that was of course suppressed mostly by violence.

The same thing shows up in the American Revolution a century later. David points out it’s a deep part of the Enlightenment. One of the striking points that he makes in the essay is that these concepts of human rights, Enlightenment, justice and so on, appeared in what’s called the West only at the time when they came into confrontation with other societies and cultures. In the whole long period before that, nobody ever bothered with such things. That can’t just be an accident. And I think we see it right through history, in a way, back to Aristotle’s Politics.

Betsimisaraka women in Madagascar, c. 1900. Public domain. A subset of the Betsimisaraka, termed the zana-malata, were the focus of David Graeber’s dissertation research, from which Pirate Enlightenment is derived

ND I found it very interesting how David links gender politics and the social status of women. Western societies in general are patriarchal, but the communities in Madagascar described by David in his book are not, so it is odd that it is us who are considered to be democratic.

NC Actually, that has very interesting, very current implications. The Roe v. Wade case, if you read [Supreme Court Justice Samuel] Alito’s actual opinion, his decision, is quite interesting. What he says is that there’s nothing in history and tradition that supports the idea that women have rights, which is quite true. If you look back at the constitution, the framers – for them women weren’t even persons. They were property. That’s Blackstone [Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1765–69, by William Blackstone], English common law. Women are property owned by the father and handed over to the husband.

One of the arguments against allowing women to vote in the constitutional debates was it’s unfair to unmarried men because a married man would have two votes: himself and his property. This runs right through American history. It isn’t until 1975 that the Supreme Court officially determined that women are people, peers, who can serve on federal juries.

So Alito’s opinion is quite right. In all of American history and tradition, there’s nothing to suggest that women have rights. Therefore, Roe is breaking from the tradition by saying, ‘Yes, women should have rights’. It’s not exactly the message he wanted to convey, but it’s the essence in which his opinion is historically accurate.

It’s basically since the 1960s that there has been real pressure for not only women’s rights, but even freedom of speech. You look back at history, there’s no history of protection of freedom of speech. You begin to get the elements of it in the twentieth century, mostly in dissents. But it was not until the 60s that there was strong public popular pressure, sufficient for the Supreme Court to take a fairly strong position.

Actually, in the current regression, major figures in the Supreme Court, Clarence Thomas, are saying they want to rethink those decisions that establish freedom of speech, like Times v. Sullivan. We may go back to the tradition, just as we’re doing with the revision of Roe. These are very tenuous achievements. We have to struggle for them every minute.

ND The Paris salons, where many of these Enlightenment ideas were formed, mostly in endless conversations, were run largely by women. David’s Pirate Enlightenment talks a lot about war. He describes how the opposing sides put coloured signs on their foreheads, blue and yellow, to be able to distinguish one another in battle. War is also a dialogue, but a masculine one, where the instruments of communication are reduced exclusively to violence. For the characters in David’s book, however, the war ends in Assemblies, which restore complex human conversations. If we think about our current situation, what is most striking is the insistence on the abandonment of all dialogue and any exchange of opinions.

NC Yeah. That’s again a very timely issue. As you know, the NATO Summit [in Madrid at the end of June] received lots of attention, very positive attention. One crucial element of it, which hasn’t received much discussion, bears exactly on what you’re talking about. If you look at the NATO strategic statement, I think it’s Article 41, the basic thrust is we cannot have discussions and negotiations about Ukraine. It must be settled by violence. Those aren’t the words that are used, but that’s the meaning of the words.

What they say is that the question of admission of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia and Ukraine into NATO is not up for discussion. No third party can have any voice in it. We will decide as we wish. That’s a way of saying, ‘There cannot be any negotiations’. It’s been understood for 30 years, long before Putin, that no Russian leader will ever accept having Georgia and Ukraine in a hostile military alliance. That would be lunacy from Russia’s strategic point of view.

Just look at a topographic map or the history of Operation Barbarossa [Nazi Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union] and you can see why. That’s been understood by high US diplomats and directors of the CIA. All of them have warned against this. But NATO, meaning the US, just decided that doesn’t matter. We’re going to continue to insist that everything be settled by violence, not by negotiations. No dialogue. It’s probably the most important part of the NATO Summit, and it’s consistent with what US policy has been. No discussion, just force.

David Graeber hosts a debate at the London School of Economics during the campus-wide programme Resist: Festival of Ideas and Actions, 2016. Photo: Peter Marshall / Alamy Live News

ND You are a prominent scholar who has worked in Western academia for many years. I know nothing about academia except that David thought it was conservative and almost reactionary, and wrote extensively about it. Perhaps the very idea that it is possible to substitute dialogue with others for direct violence while preserving democracy and freedom within our own space is shaped and supported by the Western academic community.

NC My academic life has been for 70 years at the elite institutions: Cambridge, Mass; Harvard, MIT, others like them, Oxford and so on. All the same. Ideas of this kind can scarcely penetrate. They are immune to consideration of the fact that the system that they were embedded in is based on violence and suppression. The theories that are developed, like international relations theory, completely miss much of this.

The security of the population is almost never a consideration in formation of government policy. Security of elite interest, yes. Not security of the population. In fact, this shows up very dramatically if you look at contemporary documents. Take the NATO Summit again. The phrase ‘rules-based international order’ occurs repeatedly, over and over again. We have to preserve ‘the rules-based international order’. The phrase ‘UN-based international order’ never appears, not once. There is a UN-based international order, like the UN charter, but the US doesn’t accept it. It bars all the activities that the US carries out.

The big struggle with China, ideologically, is that China is insisting on the UN-based international order. The United States wants a rules-based order. The hidden assumption is the US makes the rules. We want an international order, which is basically the mafia. The godfather makes the rules, and everybody else obeys or else. That’s the rules-based international order. And you can demonstrate that that’s the way it works, but you can’t penetrate elite discussion with this. I can talk about my own experience, but it’s just anybody in the same system can talk about it.

My apartment in Cambridge was a couple of blocks away from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. I wasn’t allowed to cross the threshold unless they couldn’t prevent it. Like, if I was invited by an international organisation or the foreign press or a student group, then they had to allow it. But otherwise it was considered contaminating the premises by even talking about these topics.

ND Sometimes it feels like we’re seriously close to the end of the world. David, however, was an eternal optimist. No matter what was going on, he would say, “Okay, let’s look on the bright side. What can we do? How can we find a way out of it?”

He tried very seriously to help [former UK Labour leader Jeremy] Corbyn, but when Corbyn got crushed, David almost fell into a depression for a while. Very soon, however, he focused on the Brain Trust Project, a group of academic and nonacademic activists and artists trying to create an independent thinktank to address climate change. Yet our current situation, the disasters we are facing on such a scale, it is difficult to keep being optimistic.

NC Whatever our personal sentiments are about the likelihood of disaster, we have to maintain the ‘optimism of the will’. There are opportunities, whatever they are, and we have to devote ourselves to them. Take Corbyn. Very significant. I mean, if Corbyn had become prime minister, as it seemed in 2017 that he might very well do, it could be a very different England. Instead of being just a vassal of the United States, which it is, it could have been an independent element in world affairs.

He could have joined with Europe to lead an independent Europe, which could have made accommodations with Russia prior to the invasion, when it was a possibility. Instead of just falling into the lap of the United States and becoming a total dependency, which is what happened.

The British establishment knew what it was doing. The establishment all the way over to The Guardian, the so-called left. It’s very dangerous to allow a person to gain power who’s trying to create a popular-based political party that will reflect the interests of its constituents instead of concentrated private power. He was succeeding in that, and that’s much too dangerous to allow.

So the whole establishment, from what’s called the left over to the right, just launched an incredible campaign to discredit him, very successfully. Totally fraudulent grounds, but a very interesting illustration of the manufacture of consent, which is much broader than just the institutional structures involved.

It’s based on a real understanding that popular power is just too dangerous to permit. It will threaten elite dominance in all domains and could lead to not only an independent popular-based democracy in England but even to independent moves in world affairs, which would undermine the mafialike structure. Quite a lot is at stake in keeping somebody like Corbyn out.

Courtesy Allen Lane

ND David vividly describes how the democratic structures of pirate communities were influenced by Madagascar’s traditions. The pirates chose a captain who had full authority over the crew during combat, but not in everyday life.

Many of these pirate traditions are strikingly similar to anarchist practices and are truly democratic, allowing each member of the community to shape the social environment around them, unlike our current ‘democracy’, which is built on institutions that prevent people from access to decisions about how they might live.

NC As he stressed greatly, you don’t have democracy if representation is of the kind that liberal theorists call for. So take the main liberal theorists of democracy, people like Walter Lippmann, for example, or Harold Lasswell, or others. In this picture, the public has a role. Their role is to show up periodically and cast their weight in favour of one or another member of the elite class that represents power, and then go home and let them run the world but don’t do anything more.

That’s what’s called democracy. And as David stressed, that has no resemblance to democracy. Democracy means direct participation in decision-making at every level. You can delegate responsibility to someone temporarily to carry out or play some administrative or another role.

For example, in the Native American tribes that he discussed, where you pick a war leader for a particular conflict and then listen to him during the conflict, then he goes back and joins everyone else. That’s like the pirates, in fact, electing a captain because they need somebody to make decisions and then take them back. But it’s the public itself that always has the power and can, if it wants, take over decision-making.

If you don’t have a structure like that, it’s not democracy. And of course, such structures can be developed. Let’s go back to Corbyn. If he had succeeded in creating the kind of Labour Party he was working for, it would have been a constituent-based party with local groups putting their input into direct decision-making and so on. It’s not what the parliamentary Labour Party wants. They want to make the decisions and everybody else should shut up and listen. That’s [Tony] Blair’s party, [Keir] Starmer’s party. The weight of the establishment was so strongly behind them that the effort to create a popular party was just crushed.

Interestingly, the campaign was successful among the constituency. I’ve talked to Labour activists who were knocking on doors. They said it really sold. People just didn’t want to hear about Corbyn, they didn’t want to hear about a four-day week or any of the economic proposals. Just save us from this person who’s trying to destroy Britain. It worked very effectively.

Welfare State rally in London, 2010. Photo: Theodore Liasi / Alamy Stock Photo

ND I want to share good news from the artworld, which is also a very powerful institution, very much like an academy, very much built on exclusion and big money, seriously connected to financial capital, taxes and, ultimately, the state. One of the largest art exhibitions in the world, Germany’s Documenta, has been curated by a collective from Indonesia, who are exhibiting almost no artwork or famous artists, in the traditional sense of the word. They invited different collectives, mostly from the Global South.

This is an amazing exhibition, in the sense that it shows not the artistic achievements of some individuals, but the useful, caring and beautiful human practices of different communities.

But then again, as with Jeremy Corbyn, they are now under tremendous attack, perhaps on the verge of being destroyed. The only hope is that, just as with Corbyn, the current exhibition in Documenta can show us a glimpse of another world, as if it were an escape route that could one day save us.

NC That’s very interesting. I remember about 20 years ago – unfortunately, I forgot the name – there was an art connoisseur, Canadian, I think, who curated exhibitions of rugs. He pointed out that for thousands of years there was a form of women’s art in the Middle East, creating these marvellous rugs with wonderful designs and structures and so on. But no one ever regarded it as art, because it was women’s work. But the materials were quite fantastic. He ran into plenty of resistance. Who cares about rugs? But if you look at Oriental rugs, they’re quite amazing. By now, this artform is disappearing because it’s being replaced by commercialised duplicates. But for literally thousands of years, it was a major collective creative artform. Individuals would create their own art. They would work with each other. Because, of course, it’s collective, you can’t make a rug yourself. They made some remarkable contributions to women’s work.

ND The artworld first and foremost stands for the separation of production and consumption so it is difficult for it to relate to collective works. Therefore, a significant artist, in the Western sense, is always a loner who is distinct from the rest of us. But the industrial workers, who collectively produce things we use every day, remain anonymous. The same separation results in all of us staying as spectators and consumers, and without engaging in collaborative creativity. Documenta 15 had changed this narrative. It brought to Germany artists from Bangladesh, Latin America, African countries, and their real stories of fighting for freedom, caring for children, cooking food and so on. They showed us Westerners that most people in the world are, in a sense, better off than we are, despite their lack of the art institutions, if only because a core value of their art is care.

NC I saw something a little bit like that at the World Social Forum back 20 years ago. The first meeting of the World Social Forum, in Porto Alegre, Brazil. One of the collaborators was Via Campesina, the world’s major international peasant organisation. It facilitated areas where mostly women set up tables and shared their cultures – different societies, different languages, different ways of cooking, different kinds of seeds, and a lot of complex lore and understanding.

In fact, for the most part agriculture was a scientific activity in the hands of women. A woman would hand the knowledge down to her daughter, which seed you plant on which side of the hill because it gets the sun in the afternoon and all that kind of stuff. In fact, when scientific agriculture came in, it lowered yields because all of this knowledge was lost. But in these meetings of Via Campesina, it was all being brought back with individual understanding, complicated culinary arts, building things and exchanging ideas. It was quite amazing to watch. It’s disappearing, of course. The World Social Forum doesn’t have it anymore.

ND In Pirate Enlightenment, David describes a Marxist attitude to Madagascar’s history, where the main driving force is the struggle of the elites among themselves for the expansion of power.

David notes that it is a little strange to assume that any society is built according to this principle. But today’s Russia follows this logic: actively participating in the struggle between rival elites.

In the 1960s, the USSR pursued a different goal, supporting anticolonial movements worldwide with finance and arms.

NC Remember that Russia itself is an imperial system. You go back to the Duchy of Muscovy, which expanded over much of the world: all imperial conquests. There’s an interesting book, if you haven’t seen it yet, Crusade and Jihad [2018], by William Polk, a great historian who died recently, which is about the thousand-year war of the north, including Russia, against the mostly Muslim south. That’s why the regions that Putin is visiting right now [in July] are Muslim. They were all conquered within the expanding Russian empire. What we talk about as Russia, it’s like the United States. We think of the United States as a sovereign country, but only after it exterminated the inhabitants. Russia didn’t exterminate them, but it incorporated them.

It’s an imperial system, to begin with. And it’s mostly a war against the Global South, which happens to be mostly Muslim. As Polk discusses, it’s a major theme of the history of the past thousand years. Every form of resistance has been tried, and they all failed and end up being jihadis. That’s part of the sweep of world history. What’s bothering the West now is that it’s encroaching into Western territory. That you’re not allowed to do. You can kill anyone you want somewhere else, just the way we do. It’s very interesting to watch the reaction of the Global South to this conflict.

You read Western journals. They can’t understand why the countries of the Global South aren’t joining in with us. But these countries are laughing. What they say is, “Yes, of course it’s aggression, but what are you guys talking about? This is what you do to us all the time. We’re not going to join your crusade.”

ND A friend of mine who lives in the Middle East said: “With horror everyone watches white people kill white people. We’ve been living like this for a long time.”

NC David’s insights into all of this are very illuminating, and it undercuts a lot of conventional thinking. Also just pointing out the many options that there are for developing more enlightened, more free societies, not just the ones encoded in our artificial traditions, which exclude lots of what happened and reshape the rest into fitting into convenient frames for existing power systems. I think that’s a tremendous contribution.